Online Talks & Fun Presentations

“M’gog has a natural teaching ability that isn’t directed by the norms of education today, but appeals to how we, as inquisitive humans, want to learn. Her capacity of putting this to paper is an invaluable skill.”

Robyn Hartley

An Island Home

For two and a half years, I lived on a small island in the White Nile. No name, no address. Just a thumbprint of land, about the size of four tennis courts, surrounded by river and sky.

It was just me and my two dogs — Dante and Nibbit. They weren’t mine, not at first. But they followed me onto the island, took one look at the rat situation, and got to work. Within a week, the rats were gone. The island was ours.

Thirty kilometres downstream from Jinja, the river here is wide and muscled. Just 600m downstream from me was Nile Special, one of the best standing waves in the world for freestyle kayaking. Bell’s Hole sat just beyond, and when the dam upstream caused shallow water downstream, Club Wave would appear like a rumour. I watched the river like you might watch a mood: curious, alert, never quite knowing what would happen next.

My days were simple, but not quiet. The river doesn’t whisper. It moves. It thrums. I ate tomatoes and aubergines, mostly. I boiled river water for tea. Once a month I’d catch a boda-boda (motorbike taxi) to Jinja — four days to stock up on dry goods, read my emails, see friends and have a red wine and a steak!

I had no fridge on the island. No running water. But there was an ant-free table — its legs standing in tin cans filled with water, like stilts in a tidepool. It worked. I kept my food ant-free.

I started kayaking. Badly at first. I taught myself to roll, sometimes upside-down longer than planned, shunted through rapids in a boat I couldn’t yet control. I’d paddle down through Nile Special, get spat out grinning and breathless, drift to the Hairy Lemon — a jungle lodge for kayakers a kilometre downstream. The trip down took just minutes. Coming back up took an hour. It was worth it.

In the northern winters, paddlers from all over the world would turn up to surf the wave. We’d meet out there — half shouting over the roar, half sharing a rhythm. The rest of the year, it was just me, the river, and the dogs. I once went six weeks without seeing another person.

The days didn’t stack up like normal time. They floated. One into the next. Light into dark. Paddle into firewood into rain. I read books. I wrote things down. I tried things just to see if I could.

But mostly, I lived.

And the river carried everything else away.

Touching Trunks

Rubondo Island isn’t the kind of place you stumble upon. It’s a destination you seek — deliberately, almost reverently. So there we were, myself and a family of four, making our way to this remote island in Tanzania, set like a green jewel in the vastness of Lake Victoria.

Rubondo has a story to tell, whispered through forest canopies and reed beds. It’s where elephants, chimpanzees, and the elusive, water-loving sitatunga were once introduced, not for tourism, but as a lifeline — an insurance policy for a world where extinction was becoming a real threat.

We arrived just as the sun tipped into dusk, turning the horizon to fire. The sandy beach blushed red beneath our feet, and the world took on that hushed, golden pause that comes just before nightfall. Then, as if conjured by the silence, a hippo and her calf emerged from the water and began to shuffle along the shoreline. Not ten metres behind them, three bush pigs trotted with an air of mischief. No crowds. No noise. Just us and a living, breathing fragment of Eden.

But we hadn’t come for bush pigs. We were here for the elephants. On Rubondo, they’re not the habituated, safari-seasoned giants of the mainland. Here, they utilise the whole island — forest, swamp, the tiny wooded savannah and shoreline. They’re self-willed and not entirely used to people, which makes finding them more of an art than a science. We crossed fingers. We crossed toes.

And then we saw them.

A herd, deep in the forest, threading between trees with an air of ancient certainty. Among them, a few young males — full of hormones and hubris. One decided to show off.

We cut the engine. Sat quiet.

He began pushing at trees, testing his strength and maybe our nerve. Closer, closer… until one last shove brought him barely three metres from the car. His ears flared wide, a branch thrashed sideways, and he stepped into our silence.

One metre from the bonnet.

We held our breath.

Then two others joined—curious, emboldened, rumbling low and watching us with the intense eyes only elephants have. It felt less like a threat, more like a standoff: Who are you? Why are you here?

We didn’t move.

Eventually, with the theatre of true wildness, they turned. Not before dropping the tree they’d been arguing with. Thankfully, it fell on a slant — more gesture than danger.

They vanished as silently as they’d come.

That’s the Rubondo difference. It’s not a checklist safari. It’s not predictable. It’s elemental. You meet animals on their terms — raw, real, and utterly unforgettable.

Would I go back? In a heartbeat.

Ndege News

As the editor of Ndege News, the in-flight magazine for Air Kenya, Regional Air in

Tanzania and Aerolink in Uganda, its my job to not only put together and edit the

magazine, but also to create interesting graphics and to decide which stories and

places should be featured to showcase the amazing diversity across this part of Africa.

Frozen Still

the meeting of a leopard

I’m housesitting this gorgeous place up in El Karama. It’s built like a lodge, surrounded by incredible wildlife. Part of the job includes looking after two little terrier dogs. This adds a layer of caution because, well, leopards are around, and they love snacking on small terriers.

A friend came to overlap for three days to learn the ropes with the dogs so I seized the chance I’d been dying for: to sleep outside! My chosen spot? A bench by the beautiful infinity pool up at the top of the property.

Saturday meant friends and a few beers – and for me, “a few beers” is always a few too many because I’m hopeless at drinking! By 9pm, I was completely exhausted, dehydrated, and had a stomping headache. My bed called …

The pool is about 100 metres from the main house, reached by a long U-shaped path, though there are a couple of shortcuts. Midnight arrived and my headache had not abated … The Panadol was down at the main house. It was such a beautiful night, I figured I didn’t even need a torch.

I slipped out into the moonlight, I didn’t want my flip-flops because I’d have to walk past the dogs’ bedroom. If they heard me, they’d bark. Aching head … no glasses … I reached the first shortcut … I took just two steps when, suddenly, at my left shoulder – sitting on a rocky outcrop – was a female leopard. I quickly looked to the ground and away.

She snarled! A surprised, angry, spine-tingling snarl …

“I was literally so close I could have reached out and touched her.”

I knew that snarl – it was a proper “snarl to kill.”

“I’m sorry, Miss Leopard,” I said. “I’m very sorry. I just… I’ve got a roaring headache. I need Panadol. I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to take a shortcut”.

Nothing. I didn’t dare look nor move. My heart racing.

“Look, I’m going to take two steps backwards. Back onto the main path. Just … I’m gonna walk away.”

I took two steps back and stopped. She gave this low growl.

That told me, okay, that’s alright.

Breathless, I reached the main house, and took my paracetamol. Then I thought, there is absolutely no way I’m going back up there again. I’d have to walk right past her.

I’d have to sleep down here. Of course, my duvet was up at the pool. I ended up getting two carpets and wrapping myself up in them, sleeping on the sofa outside on the verandah of the main house.

And wouldn’t you know it? On the one night I’m struggling with a throbbing headache because of two beers, everything decides to come alive. Next thing, a hippo comes grunting past. “Grunt, grunt, grunt.” I’m thinking, “come on, I’m trying to sleep!”.

Then three hyenas kill an African scrub hare, causing a load of commotion.

And then, a whole herd of elephants appears at the water hole!

All I wanted was a good night’s sleep.

Eventually, I must have fallen asleep. The next day, we checked the camera traps. And yes, the photo you see? That’s the camera trap picture of the leopard.

Lion at the Door

Imagine this: it’s 4 o’clock in the morning in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. The air is cool, the stars bright, the bush quiet. I was running a field research centre there, north of Maun. My favourite part of the day was this quiet hour, 4 to 5 am, before the students were up, where I could just have a cup of tea and soak it all in. These mornings often held incredible moments – a lioness walking past roaring just metres away, or finding myself in the middle of a pack of African wild dogs as they chased down and killed an impala right near me.

My routine was set: up at 4, quiet hour, then prepping breakfast at 5, and waking the “studelbugs” at 5:30 so we could be out by six. Waking them up meant going to their separate huts. Elephants and lions were often around our camp, so you had to be careful.

One particular morning, I got up at 4, ready for my tea, and went to open my door. My house was one of those wooden A-frame structures with canvas sides and a proper wooden door. I pushed, but the door wouldn’t open. “That’s a bit bizarre,” I thought. I messed around a bit, brushed my teeth, and tried again. Still wouldn’t budge.

Feeling it was very strange, I decided to peer out. You could roll up the canvas sides, though not open the netting. As I looked out, I saw him: a great big male lion. He was sound asleep on my porch, leaning right against the door. I couldn’t open it because he was blocking it!

I got back into bed, thinking he’d leave soon and I’d just miss my tea and be a bit late. But 5 o’clock came, and he was still there. The closest student hut was maybe 50m away, and others were further. I had to let them know I couldn’t come and get them.

I’d never tried shouting over a big male lion before. How loud could I be before he got annoyed? I wasn’t too worried – these lions are often quite lazy. I attempted a shout, “Studelbugs! I can’t come and get you!”.

“What? M’gog, we can’t hear you!” came the faint reply.

Finally, I got the message across. And the lion? He didn’t even budge. My message to them was clear: “Don’t move. We’re not going out this morning. There’s a lion blocking my door!”

Finally, around 8am, he stood up. I was back in bed by then, reading a book and looking out the low netting window onto the porch. He stretched, didn’t even glance in at me, and then padded off down the three little stairs to the ground.

I gave him some time, then finally opened the door. The wood was still warm from where he’d been lying. I went off to get the students, and shared this incredible story.

It’s just amazing to think about. A lion was sleeping at my door, less than 3 metres from the bottom of my feet. I didn’t hear him arrive, so he could have been there all night, just deciding my porch was a good spot for a nap.

Absolutely amazing.

A Leopard Amongst the cows

We were camping just off the Central Kalahari Game Reserve in Botswana, a two-month study abroad course with a dozen students. At one point we set up camp on the grounds of a cattle farm, offering us a chance to look at the beef industry and the impact of farming near wildlife areas.

At dusk, the cattle were herded into a boma (a wooden stockade protection against predators). My tent was set beneath a thorn tree, slightly apart from the main student rows. Most nights, we’d be exhausted and in bed by 8 pm, but on this particular night, I was up past midnight, trying to figure out which of my students was up to some kind of mischief. When I finally turned in I slept deep – snuggled in my sleeping bag because it was the cold, winter season.

Then, suddenly, I heard a huge hullabaloo. I only found out later the cause: a leopard had gotten into the boma and panicked the cattle. In a frenzy, they broke out of the boma, and chaos erupted.

Still deep in sleep, I couldn’t make sense of the noise.

The next thing I knew, completely instinctively, I felt myself curling up into a ball and throwing myself across to one corner of the tent. I can only assume my body knew what was about to happen.

Seconds later, a massive bull landed directly on my tent, kicking and thrashing. A tent pole broke, and the fabric began ripping. I was zipped inside, unable to see clearly or get my bearings, just curled up, now wide awake and absolutely terrified.

Eventually, the bull got up. I could hear its noises and realised it was indeed a bull. My heart was hammering, adrenaline surging. There was noise outside – students shouting, trying to figure out what was going on.

Things eventually calmed down. I managed to get out of my ruined tent. I learnt that the leopard had caused the scattering of the cattle.

Despite the chaos and the damage (one pole bent, one broken, the tent ripped but still somewhat functional), I climbed back in to sleep. My bedding was in there, and frankly, what else was I going to do?

Lying there, it hit me. After traveling to amazing places, seeing incredible wildlife, imagine telling my parents their daughter was killed because a huge bull, weighing a ton, a big, solid, fattened bullock – landed on her.

It would have been madness!

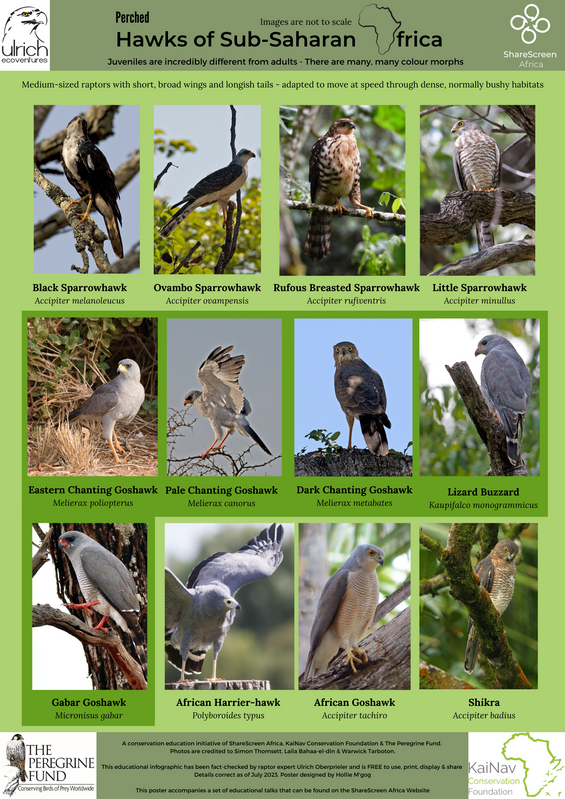

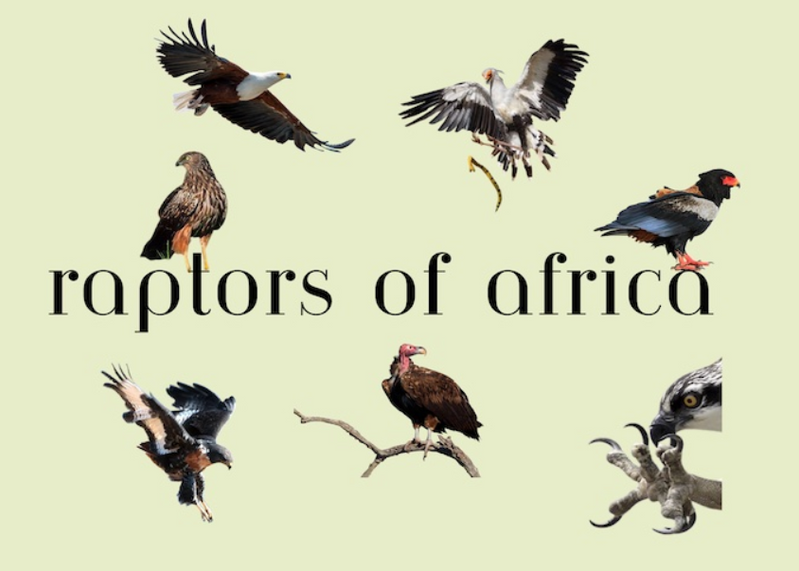

Raptors: The True stars of the Bird Kingdom

Silent watchers in the sky,

With powerful wings they circle high —

Martial eagles, bold and white,

Scan the land far and wide.

A lanner stoops in sudden grace,

Tearing silence, slicing space.

Secretary strides with steely tread,

Striking fear where cobras tread.

Fish eagles cry by lakeside light,

Their echoes stitched through morning flight.

Vultures spiral, patient, grim,

Nature’s keepers, sharp and trim.

Africa’s raptors — keen of eye —

Masters of the wind-swept sky.

Not just hunters, fierce and free,

But balance keepers through history.

BBC Wildlife

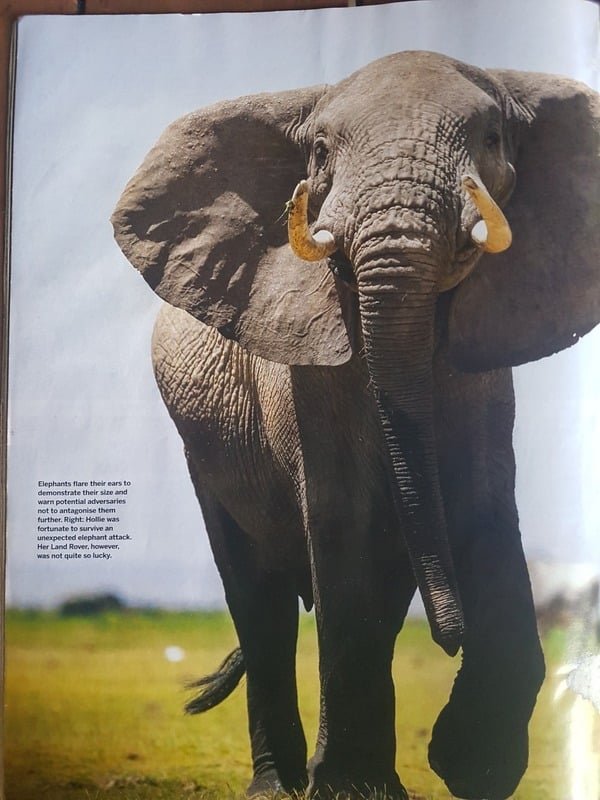

An Elephant through the

Windshield

It started like any other field day: six students and me, out in the wilds of Khwai, about four kilometres from camp, setting camera traps under the wide Botswana sky. We were riding in our latest acquisition — a gleaming second-hand Land Rover with an open back. The students were perched high, buzzing with energy, cameras ready. The landscape was stunning, the sort of place where you feel the bush breathing. But the elephants — well, they’d been different lately. Edgy. Twitchy. And that meant we kept our distance.

We were heading back to camp when the air shifted.

Up ahead, maybe 80 metres down the sandy track, a herd appeared — elephants, moving with intent, crossing fast toward the river. We stopped. Engine off. Silence. Most of the herd passed quickly, kicking up dust and tension.

Then came the teenager.

He burst out from the bush on our right, ears wide, eyes locked, charging straight at us. Just a young bull — but full of swagger and unpredictable hormones. I slapped the side of the Land Rover hard, shouted loud to rattle him, and told the students to hold steady. “It’s just a mock charge!” I said.

He skidded to a halt — just a metre from my window.

Massive. Breathing heavy. Testing us.

He backed off.

Then came again.

After a tense pause, he veered in front of us and headed down the road. We all exhaled — he’s leaving, we thought.

Wrong.

He spun on a dime and came crashing back, tusks low, slamming into the front of the vehicle. The impact rattled through the chassis. I tried to keep calm, reassured the students again—“He’s just scared himself,” I said. “Elephants don’t really charge cars.”

Except this one did. Again.

And then again.

On his third pass, I knew we couldn’t sit there and wait. I threw the Land Rover into reverse and floored it. The next moments were a blur. I believe the elephant lifted the front end of the car, shoving us backward while I reversed at 40 kph. We weren’t even on the road anymore — I was just trying not to crash.

But we did. Straight into a tree.

The car stopped dead. The elephant didn’t.

Momentum carried him forward — straight through the windscreen. I saw his left tusk coming, fixated on it. The glass splintered, then shattered. I ducked. Just in time. The tusk clipped the top of my hat, tearing a hole that’s still there today. Then he ripped the entire roof off the cab like it was cardboard.

Behind me, the students, from their angle, saw the right tusk spear into the passenger seat — and for a moment, they thought it had gone through me.

The elephant backed off, circled, and hit us again — this time from the passenger side. The car tilted dangerously, lifting to an angle of nearly 70 degrees. I shouted: “Everyone out—now!”

They leapt, tumbled, scrambled — we split and ran, myself and three diving into the nearest bush just five metres behind the car.

But he wasn’t finished.

Even with us hidden, he kept at it — puncturing the diesel tank. In one final, almost deliberate move, he lifted the Land Rover and set it down on a tree stump.

We huddled, frozen, barely breathing. Ten, maybe fifteen minutes passed.

Then, at last, he trotted off into the mopane.

We emerged slowly, stiff, stunned, trembling. The vehicle was a wreck.

Miraculously, a Land Rover from a distant camp appeared on the road — pure chance. But here we were. We piled in, returned to the wreck to collect what we could, and finally made it back to camp.

A medevac chopper arrived. No major injuries — just rattled bones and frayed nerves. Dave had a sore back from the tree impact, but the spare tyre had taken the worst of it.

That night, against all logic, we rinsed off the spaghetti salad that had exploded during the chaos and ate it, noticing the grit. Only in the morning did we realise it wasn’t sand — it was shards of windscreen glass.

Looking back, it was the closest I’ve come to dying in the bush.

But we made it.

It’s a brutal reminder of how fragile we are out here — and how fast the wild can turn. A story of survival, certainly. But also of respect, for a world that doesn’t play by our rules.

An Oceanside Home

Playing with AI to make a song that reflects all my great memories.

I live in a little house on a coral cliff,

Views over the Ocean where tides always shift.

Waves crash into the undercut beneath my feet,

And the breeze whispers secrets, wild and sweet.

Sharky, the three-legged dog, found her peace with me,

She curls on her cushion, happy as can be.

Each evening at six, we walk along the shore,

The ocean calls to us — Sharky always wants more.

Boots, the ginger cat, lazy on my bed,

When he hears the fridge, he raises his head.

He drinks his milk while I sip my tea,

And watches the world from his place with me.

Tangawezi, small and quick, chases geckos with delight,

She naps in her hammock, tucked in tight.

A tiny little warrior, she pounces and plays,

Using my house for fun-filled days.

The monkeys, playful, bounce on my bed,

Sykes with their chatter, Vervets with their dread.

They leave little surprises, too cheeky to tell,

Their antics and mischief, impossible to quell.

A coconut crab or three, have visited me too,

They sneak in at night when the dishes are due.

Blue and red-headed agamas, sunning on my stone,

Scampering off when Boots comes along.

Sometimes, speckled green snakes fall from the thatch,

Their colours and movements so beautiful to watch.

Harmless and quiet, they melt away,

A special brief visitor in the light of day.

Any cut veggies go to the tortoises, nine in all,

They eat them slow, never in a rush at all.

Each morning, I drink my tea in the pool,

While the monkeys leap and the chickens scratch cool.

One night, I caught a honey badger on camera,

There are genets and bushbabies, pouch rats and squirrels

Monitor lizards dart across the ground,

In this patch of wildness, they’re often found.

The ocean, the animals, the quiet and the sound,

These memories are where my peace is found.

But now I’m leaving and won’t be back.

I’ll sing my song again along a different track.

Once I lived in a little house on a coral cliff,

Looking over the Indian Ocean, where the waves would constantly shift.

The tide crashed against the undercut beneath my feet,

And the breeze whispered secrets, wild and sweet.

Farewell to Boots, my ginger cat so bold,

Who’d talk to me daily, it never grew old.

And Tangawezi, the small cat with flair,

Chasing her geckos without a care.

Sharky, on three legs, with heart full of grace,

Walking beside me, she found her place.

I’ll carry them with me, wherever I roam,

These companions, my family from my ocean-side home.